En 1356, pendant la guerre de Cent ans contre les anglais, Philippe, âgé de 14 ans et dernier fils du roi de France Jean le Bon, tente de détourner les coups contre son père et gagne alors le nom de « Hardi ». A leur retour, Jean récompense son fils en lui donnant entre autre, le gouvernement du Duché de Bourgogne.

Philippe le Hardi, qui règne de 1364 à 1404, organise son duché en réformant le Parlement, la Cour des Comptes et les Etats Généraux. Dijon en devient alors réellement la capitale et la politique menée contribue à la création en quelques décennies de l’État Bourguignon

En 1380, à la mort de Charles V, frère de Philippe le Hardi et devenu roi de France à la suite de Jean le Bon, Philippe le Hardi devient co-régent du royaume de France au nom de son neveu Charles, alors âgé de 12 ans. C’est à ce moment qu’il fonde, en 1383, la Chartreuse de Champmol qui doit ainsi manifester dans Dijon l’implantation de la nouvelle dynastie. Elle accueillera la nécropole familiale, en rupture avec la tradition des ducs Capétiens, ensevelis à Cîteaux.

En 1388, Charles VI décide de gouverner par lui-même et clôt la période de régence. Mais à partir de 1392 souffrant probablement d’un trouble bipolaire, il manifeste des crises de folie et les affaires du royaume sont alors à nouveau gérées par un conseil de régence présidé par la reine Isabeau. La reine étant piètre politique, c’est encore Philippe le Hardi qui a l’influence prépondérante dans les affaires du Royaume. Quand il meurt, son fils Jean sans Peur prend la succession du Duché. Néanmoins il perd l’influence de la Bourgogne auprès de la reine dans le Conseil de Régence.

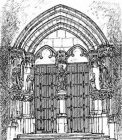

Pendant plus de vingt ans, le Duc Philippe le Hardi a consacré des sommes considérables à la construction et à l’embellissement de la Chartreuse, ainsi qu’à la constitution du domaine foncier qui fera la prospérité de l’établissement. Architectes, sculpteurs, peintres, menuisiers, verriers, tuiliers, participent pendant plusieurs décennies à la construction et au décor de la Chartreuse, qui apparaît de nos jours comme l’un des foyers essentiels de l’art occidental des années 1380-1410. Drouet de Dammartin, assistant de l’architecte du Louvre, dirigea tous les travaux de construction de la chapelle et des tombeaux. Claus Sluter, sculpteur Hollandais, imprima sa puissante personnalité à l’ensemble du chantier, et plus particulièrement au Puits de Moïse et au portail de la chapelle.

En 1410, le tombeau de Philippe le Hardi est installé dans l’église. La Chartreuse accueillit les sépultures des membres de la famille ducale jusqu’au rattachement de la Bourgogne au royaume de France, en 1477.

Vouée à la prière solitaire des moines, la Chartreuse est au XVème siècle un lieu de pèlerinage. Des indulgences papales exemptaient de cent jours de pénitence toute personne la visitant lors des principales fêtes religieuses. Au centre du cloître, le calvaire étant le but majeur de ces pèlerinages. Jusqu’à la Révolution, la Chartreuse restera marquée par le souvenir des Ducs de Bourgogne. Les rois de France, leurs héritiers, confirmèrent tous ses privilèges et y feront presque tous des visites.

A la période révolutionnaire, la Chartreuse comme tous les biens ecclésiastiques, a été mise à la disposition de la Nation et les moines ont été chassés. Le couvent des Chartreux est fermé dès 1790 et beaucoup d’œuvres sont vendues, données ou emportées par les religieux. Vendue comme bien national en mai 1791, elle a été presque entièrement démolie à l’exception du « Puits de Moïse » et du « Portail de la Chapelle ». Les tombeaux des Ducs de Bourgogne, les retables sculptés et peints seront déposés au milieu du XIXe siècle au musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon.

En 1833 le département devient propriétaire du domaine principal et décide d’établir un hospice départemental. L’architecte Pierre-Paul Petit édifie un hôpital qui allie les préoccupations de fonctionnalité et d’hygiène avec une habile intégration des vestiges. C’est ainsi que le Puits de Moïse se trouve au centre d’une cour évoquant l’espace du cloître pour lequel il avait été conçu, et que le portail retrouve sa fonction d’entrée pour la nouvelle chapelle de l’hôpital.

En savoir plus…

Le monde rural du XIIe au XVIIIe siècle avec Laurent GUYOT (octobre 2019)

|

History In 1356, during the Hundred Years’ War against the English, Philip, aged 14 and youngest son of the French King, John the Good, tried to deflect the blows against his father and then earned the nickname of “the Bold”. Upon their return, John rewarded his son by granting him, among other things, the governance of the Duchy of Burgundy. Philip the Bold, who reigned from 1364 to 1404, organized his duchy by reforming the Parliament, the Court of Auditors and the General Estates. Then Dijon truly became the capital and the policies conducted contributed to the creation of the Burgundy State within a few decades. In 1380, upon the death of Charles V, brother of Philip the Bold and who had become the King of France following John the Good, Philip the Bold became co-ruler of the French Kingdom in the name of Charles, his nephew, aged 12. It was at this time that he established, in 1383, the Charterhouse of Champmol which was intended to establish a new dynasty in Dijon. It will become the family necropolis, breaking with the Capetian dukes tradition, buried in Citeaux. In 1388, Charles VI decided to govern by himself and ended the regency period. But from 1392, probably suffering from a bipolar disorder, he experienced fits of madness and affairs of the kingdom were then managed again by a council of regency, chaired by Queen Isabeau. The queen being a poor politician, it was again Philip the Bold who had the preponderant influence in the kingdom’s affairs. When he died, his son John the Fearless took over the duchy. Nevertheless, he lost Burgundy’s influence to the queen in the Regency Council. For over twenty years, the duke Philip the Bold has devoted considerable sums to the building and beautification of the Charterhouse, as well as the constitution of the land that will make the establishment prosper. Architects, sculptors, painters, carpenters, glassmakers, tile-makers participated for several decades in the construction and decoration of the Charterhouse, which nowadays appears like one of the most important centers of Western art from 1380-1410. Drouet de Dammartin, architect’s assistant of the Louvre, supervised all construction work on the chapel and tombs. Claus Sluter, Dutch sculptor, left a mark of his powerful personality on the entire project, and particularly on the Well of Moses and the chapel doorway. In 1410, the tomb of Philip the Bold was installed in the church. The Charterhouse hosted the burial places of members of the ducal family until Burgundy joined the kingdom of France in 1477. Dedicated to the solitary prayer of monks, the Charterhouse was a place of pilgrimage in the 15th century. Papal indulgences exempted anyone visiting on the main religious feasts from a hundred days’ penance . In the center of the cloister, there is the calvary, the main purpose of these pilgrimages. Until the French Revolution, the Charterhouse was marked by the memory of the Dukes of Burgundy. The kings of France, their heirs, confirmed all its privileges and almost all of them would be visiting. During the revolutionary period, the Charterhouse, like all ecclesiastical property, was put at the disposal of the Nation and the monks were chased away. The Carthusian monastery was closed in 1790 and many artworks were sold, given away or taken away by the religious. Sold as a national property in May 1791, it has been almost entirely demolished except for “the Well of Moses” and the “Chapel Doorway”. The tombs of the Dukes of Burgundy and the sculpted and painted altarpieces were deposited in the mid-19th century in the Fine Arts Museum of Dijon. In 1833, the department became the owner of the main estate and decided to establish a departmental hospice. The architect Pierre-Paul Petit built a hospital which combines functional and hygienic concerns with a clever integration of the remains. That is how the Well of Moses found itself at the center of a courtyard evoking the cloister space for which it was designed and the doorway was again used as the entrance to the new hospital chapel. |

|

GESCHIEDENIS In 1356, tijdens de Honderdjarige Oorlog tegen de Engelsen, probeerde Philip, 14 jaar oud en jongste zoon van de Franse koning Jan de Goede, de slagen af te leiden van zijn vader en verdiende toen de bijnaam « de Stoute ». Bij hun terugkeer beloonde Jan zijn zoon door hem onder andere het bestuur van het hertogdom Bourgondië te geven. Philip de Stoute, die regeerde van 1364 tot 1404, organiseerde zijn hertogdom door het Parlement, de Rekenkamer en de Algemene Staten te hervormen. Dijon werd toen echt de hoofdstad, en het gevoerde beleid droeg bij aan de oprichting van de Staat Bourgondië binnen enkele decennia. In 1380, bij de dood van Karel V, de broer van Philip de Stoute en de koning van Frankrijk geworden na Jan de Goede, werd Philip de Stoute mede-heerser van het Franse koninkrijk namens zijn neef Charles, destijds 12 jaar oud. Het was op dat moment dat hij in 1383 het Kartuizerklooster van Champmol stichtte, dat bedoeld was om in Dijon de vestiging van de nieuwe dynastie te belichamen. Het zou de familienecropolis worden, in strijd met de traditie van de Capetingische hertogen, begraven in Cîteaux. In 1388 besloot Karel VI zelf te regeren en sloot daarmee de regentschapsperiode af. Maar vanaf 1392, waarschijnlijk lijdend aan een bipolaire stoornis, vertoonde hij waanzinnige uitbarstingen en werden de zaken van het koninkrijk opnieuw beheerd door een regentschapsraad, voorgezeten door koningin Isabeau. Aangezien de koningin een slechte politica was, was het opnieuw Philip de Stoute die de overwegende invloed had in de zaken van het koninkrijk. Toen hij stierf, nam zijn zoon Jean sans Peur het hertogdom over. Desalniettemin verloor hij de invloed van Bourgondië op de koningin in de Raad van Regering. Meer dan twintig jaar lang heeft hertog Philip de Stoute aanzienlijke bedragen besteed aan de bouw en verfraaiing van de Kartuizerklooster, evenals aan de vorming van het landgoed dat de welvaart van de instelling zou garanderen. Architecten, beeldhouwers, schilders, timmerlieden, glasblazers, dakpannenmakers namen gedurende enkele decennia deel aan de bouw en decoratie van de Kartuizerklooster, die tegenwoordig wordt beschouwd als een van de belangrijkste centra van de westerse kunst uit de jaren 1380-1410. Drouet de Dammartin, assistent van de architect van het Louvre, leidde al het bouwwerk aan de kapel en graven. Claus Sluter, Nederlandse beeldhouwer, drukte zijn krachtige persoonlijkheid uit op het hele project, en met name op de Put van Mozes en de kapeldeur. In 1410 werd het graf van Philip de Stoute geïnstalleerd in de kerk. De Kartuizerklooster herbergde de begraafplaatsen van leden van de hertogelijke familie tot de aansluiting van Bourgondië bij het koninkrijk Frankrijk in 1477. Toegewijd aan het eenzame gebed van de monniken, was de Kartuizerklooster in de 15e eeuw een bedevaartsoord. Pauselijke aflaten ontsloegen iedereen die het bezocht op de belangrijkste religieuze feesten van honderd dagen boete. In het midden van het klooster bevindt zich het kruisbeeld, het belangrijkste doel van deze bedevaarten. Tot aan de Franse Revolutie werd de Kartuizerklooster gekenmerkt door de herinnering aan de hertogen van Bourgondië. De koningen van Frankrijk, hun erfgenamen, bevestigden al haar voorrechten en bijna allen brachten ze een bezoek. Tijdens de revolutionaire periode werd de Kartuizerklooster, net als alle kerkelijke eigendommen, ter beschikking gesteld van de Natie en werden de monniken verdreven. Het kartuizerklooster werd gesloten in 1790 en veel kunstwerken werden verkocht, weggegeven of meegenomen door de religieuzen. Verkocht als nationaal bezit in mei 1791, werd het bijna volledig gesloopt, met uitzondering van « de Put van Mozes » en « de Kapeldeur ». De graven van de hertogen van Bourgondië en de gebeeldhouwde en beschilderde retabels werden in het midden van de 19e eeuw overgebracht naar het Museum voor Schone Kunsten van Dijon. In 1833 werd het departement eigenaar van het hoofdgebouw en besloot een departementaal ziekenhuis op te richten. De architect Pierre-Paul Petit bouwde een ziekenhuis dat functionaliteit en hygiënische zorgen combineert met een slimme integratie van de overblijfselen. Zo kwam de Put van Mozes in het midden van een binnenplaats te liggen die de ruimte van het klooster opriep waarvoor het was ontworpen, en het portaal werd opnieuw gebruikt als de ingang van de nieuwe ziekenhuiskapel. |